The inclusion of Poonch and Rajouri in Anantnag, while defying logic in cultural and geographical congruity, will impact voting dynamics but though the BJP relies on the Pahari vote bank in Pir Panjal, several other factors will play a key role.

A A Latif U Zaman Deva

SRINAGAR , MARCH , 05:

The upcoming parliamentary elections in Jammu & Kashmir have brought the question of delimitation of constituencies and its consequences to the centre-stage. One constituency that seems to be caught in the midst of political wrangling due to the nature of the redrawing done is the Anantnag-Poonch parliamentary constituency.

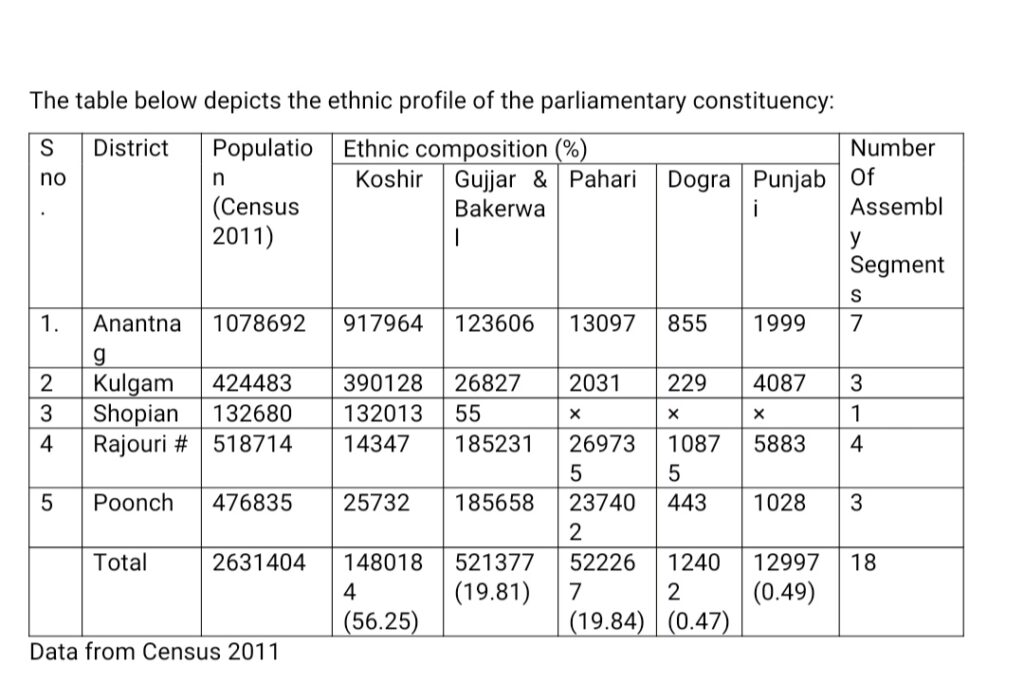

The 2022 Delimitation outlined the justification for considering Jammu and Kashmir as a unified entity for delineating Parliamentary and Legislative Assembly seats. In this report, the districts of Poonch and Rajouri were included in Anantnag, with the exception of the Kalakot Sunderbani Assembly segment. This defied logic in terms of cultural, linguistic and geographical congruity. Notably, the sole road between Anantnag and Poonch-Rajouri, passing through Shopian within the new Srinagar parliamentary constituency, becomes inaccessible during the winters.

Data from Census 2011

Note: Assembly segments Shopian and Kalakot Sunderbani fall in Parliamentary constituency Srinagar and Jammu respectively. Remaining 4% population has returned their mother tongues which aren’t prevalent in JK.

The Pahari factor

Pahari and Gujjar-Bakerwals exhibit notable differences in their aspirations, encompassing diverse cultural and customary elements. However, despite these distinctions, they share a commonality that makes them seem like two sides of the same coin in the broader context. The Gujjar community garnered significant attention starting in 1975, which intertwined the fates of both communities. This disparity became more apparent when, upon the insistence of Gujjar leadership, non-Gujjar participants were removed from Development Boards prompting the emergence of organizations advocating for the revitalization of Pahari identity. This movement eventually led to a recommendation by the State Government in 1998, urging the Union Government to grant Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to the Pahari community, along with others already under consideration before the Government of India.

While the Pahari demand was pending for decision by the State Government, ST status was extended to the Gujjar Bakerwal in 1989 by the central government, on the basis of earlier recommendations from State for it, in the backdrop of emerging political scenarios especially omens of uprising like situation in J&K.

Gujjars and Bakerwals challenge the justification given for designating Pahari as a Scheduled Tribe (ST), expressing concerns about potential job losses and diminished access to resources due to the latter’s higher socio-economic status. According to constitutional and legal provisions, sub-categorization within Scheduled Tribes (STs), Scheduled Castes (SCs), and Other Backward Classes (OBCs) can be employed to safeguard the interests of groups that have not benefited adequately based on socio-economic surveys.

However, any sub-categorization without a thorough survey may not withstand judicial scrutiny. In an election year, the ruling party may hesitate to reach out to underrepresented groups, as sub-categorizing tribes, castes, and classes may lead to opposition and a shift in loyalties. Implementing commitments to protect the share of existing ST categories might face practical challenges and, even if initiated, may be limited to Jammu and Kashmir. This could trigger ongoing uncertainties and, simultaneously, enthusiastic demands for similar considerations for SCs and OBCs facing comparable circumstances in the Union Territory.

In the districts of Poonch and Rajouri, strongholds of the Pahari rejuvenation movement, a significant number of individuals, aside from the Gujjar community, identified themselves as Pahari during the 2011 census data collection on mother tongues. However, this identification often overlooked the distinction between “ethnic Pahari” and those who merely spoke the Pahari language. The current camaraderie between ethnic Pahari individuals and non-Pahari speakers may diminish as the true definition of “ethnic Pahari” is clarified. This clarification is likely to exclude Pahari-speaking individuals who are actually of Kashmiri, Dogra, Punjabi, Arabian, Persian and other ethnic backgrounds.

The voting patterns

Paharis have consistently supported regional parties such as the National Conference (NC) and the Peoples Democratic Party (PDP). Similarly, Gujjars and Bakerwals have predominantly aligned themselves with these regional parties, with a significant inclination towards the Indian National Congress. This alignment has been strategic and purposeful, leading to the acquisition of seats traditionally strong holds of the Pahari community. However, this political landscape may undergo a shift during Assembly elections due to intra community competition in seats reserved for STs pending extension of the political reservations for ethnic Pahari community.

The rift between the Pahari community and Gujjar-Bakerwal intensified when the Government of India granted Scheduled Tribe (ST) status to the former, despite the objections raised by the latter group. This North-South-like discord might play a significant role in the upcoming elections, especially as the Pahari community is poised to support the BJP both directly and indirectly & aligning with the party’s potential allies in contested areas.

The contestation between the Pahari and Gujjar Bakerwal is evident in the latter’s predominant support for NC followed by PDP, DPAP, and Apni Party. The preference for NC over others is influenced by reports suggesting the party is fielding a candidate from the Gujjar-Bakerwal community. The BJP is expected to emerge as the highest vote-getter in the twin border districts, primarily due to Pahari support. Meanwhile, NC, PDP, DPAP, and Apni Party are likely to share the remaining 40% of the non-Pahari vote and the silent segments from Pahari community not aligned to divisive politics resulting in the vertical division of votes falling in the two border districts with minimum impact on the final results .

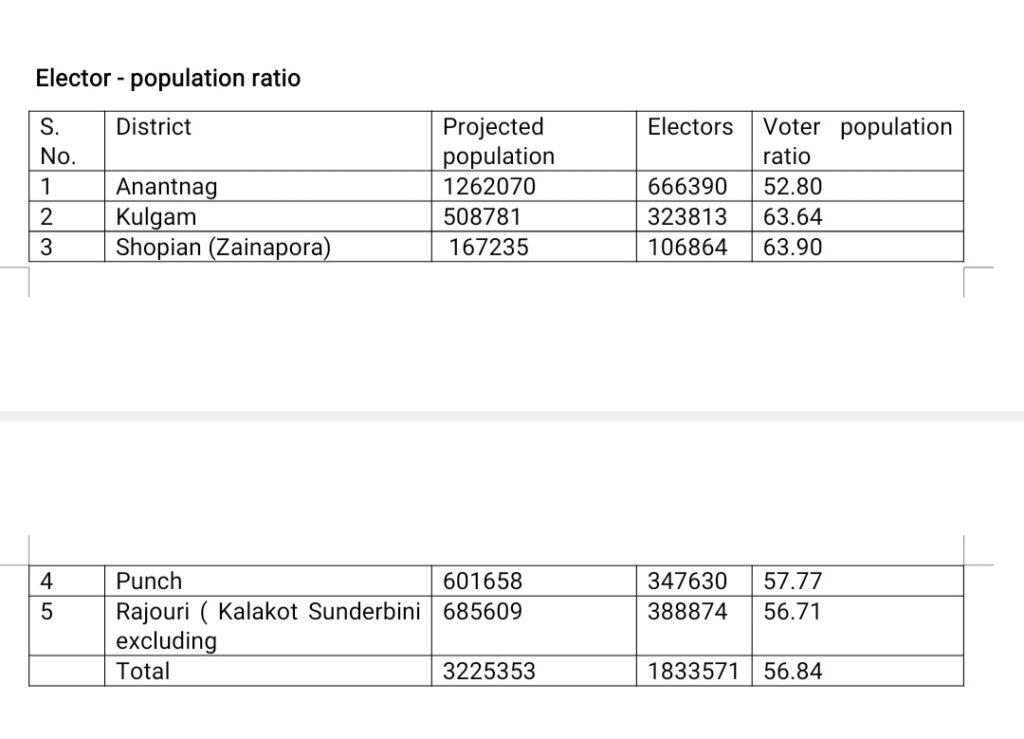

Elector – population ratio

Epicentre of electoral dynamics

The epicentre of electoral dynamics is poised to unfold in the Anantnag-Kulgam region, constituting a significant 62% of the population and a 57% voter-to-population ratio within the Parliamentary constituency. Despite a strong determination among the populace to actively participate in the voting process, challenges loom large. The concerns, such as voter turnout in this area, are anticipated to fall short of the target achievable across Peer Panchal. Additionally, there is potential fragmentation in the anti-BJP vote and the presence of a significant migrant vote bank (35,536). Furthermore, the uneven percentage distribution of voters in District Anantnag, compared to the projected population based on national/UT population-to-voter ratios, is bound to raise apprehensions.

The discrepancy in Anantnag needs to be looked into and the underlying causes addressed by conducting a special revision of the Electoral Rolls aiming at the registration of eligible individuals who were previously overlooked as voters in their respective Assembly segments. It is possible that a slight increase in the ratio may occur once the migrant population and migrant voters are accounted for in the projected populations of Anantnag, Kulgam, and Zainapora Assembly segment of Shopian Districts. Following the standard practice in Census Organizations, the migrant population has been counted at their current places of residence within J&K and throughout the country.

Quite intriguingly, the Delimitation commission overlooked the migrant population when delineating Parliamentary and Assembly constituencies in the Valley, despite their registration as voters therein. The BJP’s excess votes in border districts might have limited significance for the saffron party, given its limited primary support base in the Valley and certain pockets influenced by local body members and infrastructure development. However, the political landscape could shift with the entry of regional parties like DPAP and Apni Party, potentially narrowing the gap between the BJP and NC/PDP, the leading contenders in the Valley.

Conclusion

The outcome may hinge on effective rhetoric and oratory capturing public imagination on deoperationalisation of Article 370, straightforward political strategies, scrutiny of BJP leadership’s hypocrisy, minority marginalization, politicization of government departments, implications of authoritarianism and majoritarianism, and the future relationship with Saffronites. Additionally, the ethnolinguistic dynamics in border districts and their fallout will play a role in determining which party gains an upper hand.

The low turnout in Valley areas , a narrow gap between two regional parties, the inclination of migrant voters towards the BJP, an unexplained low voter-to-population ratio in Anantnag, indecision in INDIA alliance on seat sharing in J&K, and the division of the anti-BJP vote could create conditions for the emergence of an unexpected contender, proverbial dark horse. The public, realizing the consequences of a split in the anti-BJP vote, appears to have decided to cast their votes in large numbers for only one party, choosing between the two symbols of Kashmiri sub-nationalism.

The ability to inspire rather than incite, the support from polled votes in border districts, and the stance of the CPI(M) may play significant roles in securing a resounding victory, provided the popular mindset overcomes other reservations and consolidates votes for only one of the two regional parties.(Courtesy, Kashmir Times)

“A A Latif U Zaman Deva is a retired IAS Officer and Former Chairperson Jammu Kashmir Public Service Commission”