“Instead of focusing on manifestos, development projects, and strategies for economic growth, the election narrative has been dominated by irrelevant issues”

Latief U Zaman Deva

SRINAGAR , SEPTEMBER,16 :

Since the inception of transparency, coupled with mass participation in elections starting in 1975, an inescapable conclusion arises: non-Muslims have consistently voted for national-level parties in Jammu and Kashmir.

This trend persisted until Operation Blue Star, launched on June 3, 1984, at the Harmandir Sahib Complex in Amritsar, Punjab, significantly shifted the Sikh vote towards regional parties.

In Ladakh, the Indian National Congress (INC) and National Conference (NC) were evenly matched. However, the orchestrated anti-Muslim riots in Leh during 1989 caused a significant portion of the Muslim vote to shift from the INC to NC for a time.

From 1975 to 1983, electoral divisions between Muslims and non-Muslims were quite apparent. However, these divisions subsumed into a Hindu and non-Hindu matrix in the following decades.

This shift can be attributed to several factors, including the Punjab conflict, the rise of militancy in Jammu & Kashmir (J&K), and the growing influence of ultra-nationalism and majoritarian sentiments across India’s northern “Cow Belt”.

These movements were often in direct opposition to the secular ethos painstakingly built by Pandit Nehru and his colleagues.

Not content with the increasing foothold of Hindutva in J&K, the 2022 Delimitation Commission, backed by the BJP, resorted to gerrymandering. This redistricting process increased the number of Hindu-majority assembly segments from 25 to 31, further enhancing Hindu representation in Jammu and Kashmir.

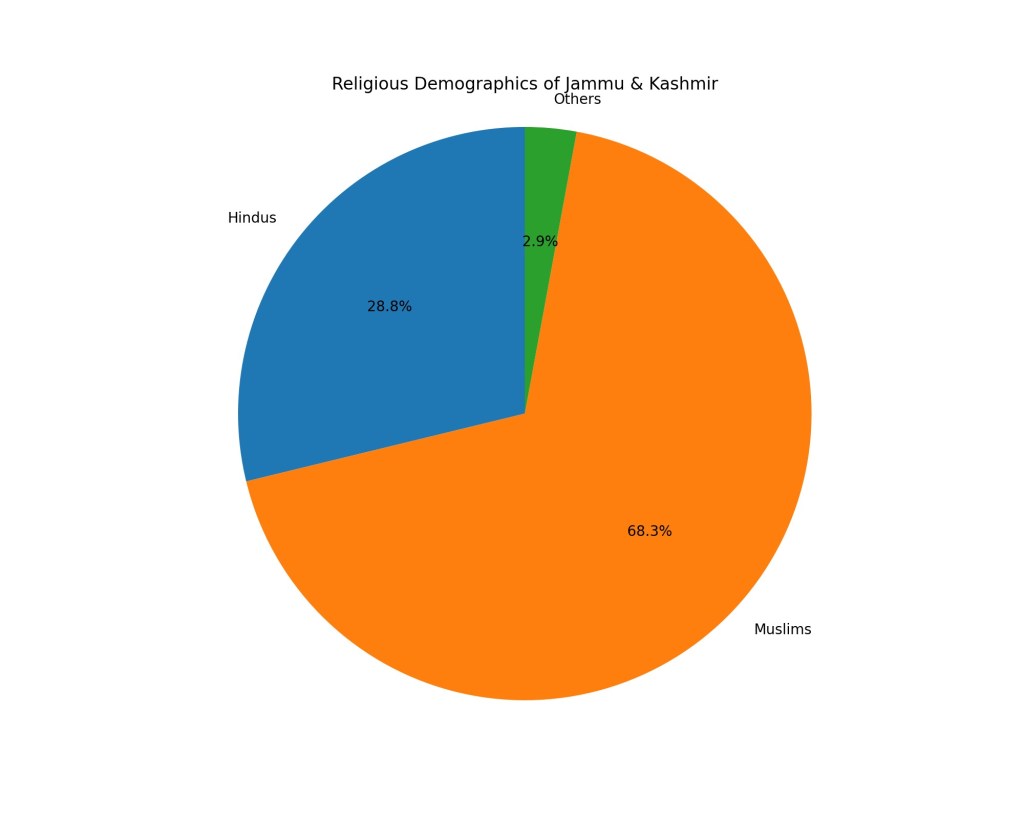

Additionally, three more segments were altered, resulting in a 50:50, which now allows Hindus, who make up 28.80% of the population, to hold 34.44% of the seats in the 90-member assembly. If the three altered seats are considered, this minority community will hold 37.77% of the seats.

The representation of Muslims in Jammu Division, who form 34.21% of the population, has significantly dropped. Through gerrymandering, Muslim-majority constituencies have been reduced from 12 to 9, and their representation has plummeted from 32.43% to 20.93%.

Further complicating the political landscape, the Lieutenant Governor (LG) will nominate five candidates (two women, two migrants, and one representative of refugees from Pakistan-occupied Kashmir).

This move has the potential to subvert the popular mandate unless rules are introduced ensuring their nomination is based on recommendations by the elected members of the Legislative Assembly. In a truly democratic setup, the LG should act on the advice of the cabinet.

The addition of five nominated members will increase the assembly’s strength from 90 to 95, with clear efforts to disproportionately benefit one particular community. This could result in 39 seats to the minority group in the 95-member assembly, compared to their legitimate share of 29 seats.

Divisions in Kashmir Valley

Even the Valley Division has not been spared, as attempts have been made to increase the population of Scheduled Tribes (STs) in specific constituencies. This move disregards principles of geographical contiguity, year-round connectivity, and the aspirations of the local people.

It has led to the exclusion of non-ST majority villages from certain constituencies, creating new problems for the inhabitants of surrounding areas.

Of the nine assembly segments with the highest percentage of ST populations, only two fall in the Valley—one each in the districts of Ganderbal and Bandipora.

However, through cunning redistricting, the Kokernag-Larnoo constituency has been reconfigured for reservation, leaving significant problems for surrounding segments.

Readers will note the stark intra-district variations in the population assigned to each constituency, which lack any logical basis.

Factors such as terrain difficulty, linguistic and ethnic concerns, poor connectivity, and geographical isolation were largely ignored, despite their importance in determining constituency boundaries.

Following the dismemberment of the State of J&K and the abrogation of Article 370, many citizens hoped to extract “democratic revenge.”

However, when the opportunity arose, they became disillusioned by the disunity within opposition ranks, leading to multi-cornered contests in most constituencies.

The August 5, 2019, decision to revoke J&K’s special status was more a rebuke to the mainstream parties than to separatists. The former had long justified their support for the Dogra Maharaja’s decision to accede to India, given the unique constitutional relationship between the state and the Union.

The traditional enthusiasm for assembly elections, last seen in 1987, has been noticeably absent in successive elections, thereafter.

This time also top leaders of contesting parties seem content with meetings of political workers rather than holding public rallies, reflecting the growing disillusionment among voters due to the failure of opposition parties to unite against the BJP.

However, this apathy does not suggest a boycott or limited participation, but rather a profound disapproval of the fragmented opposition. A larger voter turnout seems likely this time.

AIP and Jamaat Appeal

The rise of the Awami Itihad Party (AIP) and the resurgence of former Jamaat-e-Islami (JI) representatives are significant developments. However, these groups must avoid misleading voters on issues beyond the jurisdiction of the central government and Parliament.

The AIP constitution aligns with the Constitution of India and other relevant laws like other mainstream parties. Similarly, if the AIP registers with the Election Commission of India, it will contest future elections under a symbol allocated by the Commission.

Despite these developments, the active Jamaat members today do not represent the larger Islamist movement. Instead, they are a small group of individuals who have chosen the democratic route, a path to which many Jamaat supporters and other Islamists are indifferent.

This silent majority may adopt a strategy similar to that of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS), working towards societal transformation while adhering to Indian laws.

The AIP’s impact may be limited to Kupwara and parts of Baramulla, where it could potentially alter the fortunes of candidates from recognized political parties.

As I remember, during the 1983 assembly elections, Mahazi Azadi then led by political stalwart of North Kashmir, Sofi Mohammad Akbar organized a public meeting in Anantnag that attracted a highly responsive crowd of young people, urging them to boycott the elections.

Yet, by evening, many of these same participants were attending rallies for NC and INC. The emotional scenes at AIP rallies today are reminiscent of the public response to Mahazi Azadi in 1983.

In the current parliamentary campaign, one of the central messages has been the call to use democracy to secure the release of Engineer Sheikh Rashid from Tihar Jail. However, political analysts remain skeptical about the selective outrage concerning individuals facing similar charges under the Prevention of Money Laundering Act.

While figures like Shabir Ahmad Shah and Mohammed Yaseen Malik remain incarcerated, Rashid’s involvement in electoral politics and his push to restore J&K’s special status distinguish his case.

Rashid’s introduction of the state flag during protests, in place of Pakistani and Pakistan-administered Kashmir flags, marks a notable shift in the political landscape. However, some observers believe this movement will not last.

Legacy politics, opportunistic defections, and public perceptions of candidates have become central to election discourse. Khursheed Ahmed Ghanai, a retired IAS officer and former Advisor to the Governor, aptly compared this phenomenon to the “Aya Ram Gaya Ram” syndrome. Many candidates appear devoid of ideology or political convictions, driven instead by personal gain.

This political culture has led some voters, though a small number, to gravitate towards independent candidates perceived to have integrity. However, this development is concerning because it indicates a failure to rally behind seasoned politicians with a proven track record of safeguarding J&K’s identity.

Instead of focusing on manifestos, development projects, and strategies for economic growth, the election narrative has been dominated by irrelevant issues. Debates revolve around who brought the Indian Army, who eroded autonomy, and which parties lack coherent political narratives.

The Centre for Monitoring Indian Economy has noted that J&K has the highest unemployment rate in the country at 23.1%. Despite grand promises, only 414 industrial units have been registered, with an actual investment of just ₹2,518 crore—far below the proposed ₹84,544 crore.

Politics in J&K should not resemble the cynical view of American author Gore Vidal, who said:

“Politics is made up of two words: ‘Poli,’ which is Greek for ‘many,’ and ‘tics,’ which are blood-sucking insects.”

Indeed, politics is linked to society, and when it is neither vibrant nor conscientious, it results in an oppressive and collaborative setup.

As Simone de Beauvoir once observed: “The oppressor would not be so strong if he did not have accomplices among the oppressed.”

*The writer is a retired IAS officer and former Chairperson of the Jammu and Kashmir Public Service Commission.

(Courtesy: Kashmir Times)